There was once an article about Jim Davis, creator of Garfield, in which

he recognizes the recipe of his success. The trick, it seems, was to make

Garfield as inoffensive as possible. No matter what you believe, no matter how

delicate your sensitivities are, you can always read Garfield without feeling

hurt or offended. Comedians might object that a lot of humor boils down to

ridiculing something, so it's worth asking: if Garfield does not offend anyone,

how does it manage to keep being funny? The answer should be obvious to

Garfield's readers: it doesn't. Because Garfield is not funny.

The reasoning is pretty interesting: Jim Davis' goal was not to be the next

greatest American cartoonist, nor to push the boundaries of comic strips as an

art form (that would be Bill Watterson).

His goal was to make money, and boy did he succeed at that. By being a

recognizable, bland, perfectly formulaic icon, Garfield can be adopted by any

company or product willing to pay for it. The key, said Davis in this interview,

was to make the strip as plain and predictable as possible. "Oh, look,", says

the reader, "Garfield is mad because it's Monday". Cue the sound of crickets.

The same, I'm afraid, has happened to Dilbert some time ago. And while it pained

me to stop reading after so many years, I've read enough to understand that the

Dilbert I liked is gone, replaced by that which he was intended to criticize.

Including the archives, I read about 27 years worth of strips, so it was not a

decision I took lightly. That was about 4 years ago, and I haven't regretted

the decision.

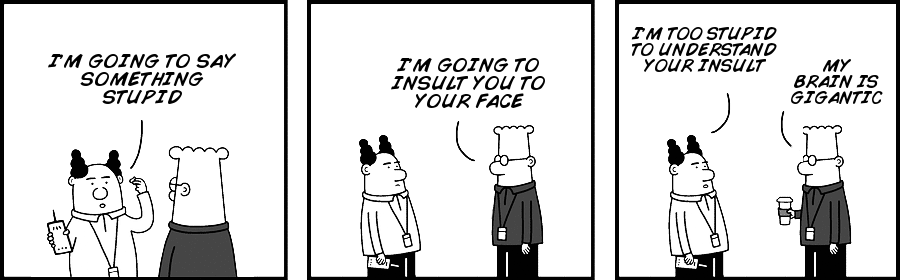

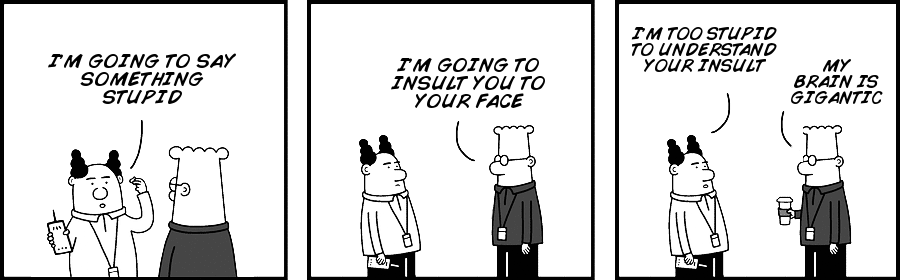

For those who might feel like me, and as a service to the community, I give you

the one and only strip you will ever need from now on. It is the culmination of

years of Dilbert, and nothing you read in the actual strip will be better than

this in the foreseeable future.

Now, in all fairness, congratulations to Scott Adams: he has managed to

secure Dilbert in the mind of the public, and he made a lot of money out of

it. It was sad to see the old Dilbert go

away, but then again, I don't have an animated series nor an (forever in

production) upcoming movie to my credit. Having said that, I can only wonder how

much more he could have produced if he hadn't rested on his laurels: his

Wikipedia achievements have almost entirely peaked around 2010, and he seems to

spend most of his time nowadays writing about what an amazing president Donald

Trump is. While this is speculation on my part, I believe this might be why his

blog is no longer featured on the Dilbert homepage.

I can see why he doesn't need to come with new ideas for Dilbert strips. After

all, he has enough money to do whatever he wants. I just wish "make Dilbert

funny again" was one of those things he cared about.

I received today the type of e-mail that we all know one day will arrive: an

e-mail where someone is trying to locate a file that doesn't exist anymore.

The problem is very simple: friends of mine are trying to download

code from https://bit.ly/2jIu1Vm to replicate results from an earlier paper,

but the link redirects to

https://bitbucket.org/villalbamartin/refexp-toolset/src/default/.

You may recognize that URL: it belongs to Bitbucket, the company that

infamously dropped their support for Mercurial a couple months

ago

despite being one of the largest Mercurial repositories on the internet.

This is the story of how I searched for that code, and even managed to recover

some of it.

Offline backup

Unlike typical stories, several backup copies of this code existed. Like most

stories, however, they all suffered terrible fates:

- There was a migration of most of our code to Github, but this specific repo

was missed because it belongs to our University group (everyone in that

group had access to it) but it was not created under the group account.

- Three physical copies of this code existed. One lived in a hard drive that

died, one lived in a hard drive that may be lost, and the third one lives

in my hard drive... but it may be missing a couple commits, because I was

not part of that project at that time.

At this point my copy is the better one, and it doesn't seem to be that

outdated. But could we do better?

Online repositories

My next step was figuring out whether a copy of this repo still exists on

the internet - it is well known that everything online is being mirrored all

the time, and it was only a question of figuring out who was more likely to have

a copy.

My first stop was

Archive Team,

from the people behind the Internet Archive.

This team famously downloaded 245K public repos from Bitbucket, and therefore

they were my first choice when checking whether someone still had a copy of our

code.

The experience yielded mixed results: accessing the repository with my browser

is impossible because the page throws a large number of

errors

related to Content Security Policy, missing resources, and deprecated

attributes. I imagine no one has looked at it in quite some time, as it is to be

expected when dealing with historical content. On the command line, however, it

mostly works: I can download the content of my repo with a single command:

hg clone --stream https://web.archive.org/web/2id_/https://bitbucket.org/villalbamartin/refexp-toolset

I say "mostly works" because my repo has a problem: it uses

sub-repositories,

which apparently Archive Team failed to archive. I can download the root

directory of my code, but important subdirectories are missing.

My second stop was the Software Heritage archive,

an initiative focused on collecting, preserving, and sharing software code in

a universal software storage archive. They partnered up with the Mercurial

hosting platform Octobus

and produced a second mirror of Bitbucket projects, most of which can be nicely

accessed via their properly-working web

interface.

For reasons I don't entirely get this web interface does not show my repo, but

luckily for us the website also provides a second, more comprehensive list of

archived repositories where

I did find a copy.

As expected, this copy suffers from the same sub-repo problem as the other one.

But if you are looking for any of the remaining 99% of code that doesn't use

subrepos, you can probably stop reading here.

Deeper into the rabbit hole

At this point, we need to bring out the big guns. Seeing as the SH/Octobus repo

is already providing me with the raw files they have, I don't think I can get

more out of them than what I currently do. The Internet Archive, on the other

hand, could still have something of use: if they crawled the entire interface

with a web crawler, I may be able to recover my code from there.

The surprisingly-long process goes like this:

first, you go to the Wayback Machine,

give them the repository address, and find the date when the repository was

crawled (you can see it in their calendar view). Then go to the

Kicking the bucket

project page, and search for a date that kind of matches that. In my case

the repository was crawled on July 6, but the raw files I was looking for where

stored in a file titled 20200707003620_2361f623. In order to identify this file I

simply went through all files created on or after July 6, downloaded their

index (in my case, the one named ITEM CDX INDEX) and used zgrep to check

whether the string refexp-toolset (the key part of the repo's name) was

contained in any of them. Once I identified the proper file, downloading the

raw 28.9 Gb WEB ARCHIVE ZST file took about a day.

Once you downloaded this file, you need to decompress it. This file is compressed

with ZST, meaning that you probably

need to install the zstd tool or similar (this one worked in Devuan, so it's

probably available in Ubuntu and Debian too). But we are not done! See, the ZST

standard allows you to use an external dictionary

without which you cannot open the WARC file (you get an Decoding error (36) : Dictionary

mismatch error). The list of all dictionaries is available at the bottom of

this list. How to identify

the correct one? In my case, the file I want to decrypt is called

bitbucket_20200707003620_2361f623.1592864269.megawarc.warc.zst, so the

correct dictionary is the one called archiveteam_bitbucket_dictionary_1592864269.zstdict.zst.

This file has a .zst extension, so don't forget to extract it too!

Once you have extracted the dictionaries, found the correct one, and extracted

the contents of your warc.zst file (unzstd -D <dictionary> <file>) it is now

time to access the file. The Webrecorder

Player didn't work too well

because the dump is too big,

but the warctools package was

helpful enough to realize... that the files I need are not in this dump either.

So that was a waste of time. On the plus side, if you ever need to extract files

from the Internet Archive, you now know how.

Final thoughts

So far I seem to have exhausted all possibilities. I imagine that someone

somewhere has a copy of Bitbucket's raw data, but I haven't managed to track

it down yet. I have opened an

issue regarding sub-repo

cloning, but I don't expect it to be picked up anytime soon.

The main lesson to take away from here is: backups! I'm not saying you need

24/7 NAS mirroring, but you need something. If we had four copies and three

of them failed, that should tell you all you need to know about the fragility

of your data.

Second, my hat goes off both to the Internet Archive team and to the

collaboration between the Software Heritage archive and Octobus.

I personally like the later more because their interface is a lot nicer (and

functional) than the Internet Archive, but I also appreciate the possibility of

downloading everything and sorting it myself.

And finally, I want to suggest that you avoid Atlassian if you can. Atlassian

has the type of business mentality that would warm Oracle's heart if they had

one. Yes, I know they bought Trello and it's hard to find a better Kanban board,

but remember that Atlassian is the company that, in no particular order,

- regularly inflicts Jira on developers worldwide,

- bought Bitbucket and then gutted it, and

- sold everyone on the promise of local hosting and then discontinued it last

week for everyone but their

wealthiest clients, forcing everyone else to move to the cloud. Did you

know that Australia has legally-mandated encryption

backdoors? And

do you want to take a guess on where Atlassian's headquarters are? Just saying.

Note: I wrote this article in August, but I didn't realize it wasn't published

until October. I kept the published date as it was, but if you didn't see it

before well, that's why.

Are you familiar with a small streaming company called "Netflix"? If so, you

might recognize their opening sound.

And even if you don't, you might have

seen one of their multiple recent press campaigns regarding this topic.

From a recent episode of the Twenty Thousand Hertz podcast

on all the sound choices that go into their logo to their announcement that

Hans Zimmer has worked on making it longer for cinema productions.

What none of those articles are saying is that this sound is also

the sound of Kevin Spacey hitting a desk at the end of Season 2 of

House of Cards. Yes,

that House of Cards, the critically-acclaimed series that made Netflix' stock jump

a 70 percent even before it started

and put Netflix on the map.

If I were a Netflix executive back then, I would be proud of having the series

as part of my corporate identity.

If I were an executive today, however, I would be terrified of people forever

remembering that my company's official sound, the one that plays before every

show, was first heard in a scene with an actor that has been very publicly

accused of sexual assault

in 2017. So I can understand why someone would feel that a change

is needed, and I'm all for it. No one is blaming Netflix (as far as I know) for

not running background checks on their actors.

Having said that, it seems that Netflix has gone all the way to completely erase

that any of this ever happened, in what has to be the most pointless

history rewrites in some time. In the above-mentioned podcast, a sound engineer

talks about all the sounds that came together to compose the current Netflix sound,

from a ring on a cabinet to the sound of an anvil, with no mention whatsoever

of Kevin Spacey hitting any desks.

Suffice to say, I was confused by this omission, so I dug a bit more and found

a Facebook post from August 2019 from the

Twenty Thousand Hertz podcast official account, where they posted:

"I'm convinced the @netflix sonic logo was originally built from Frank Underwood banging on

the desk at the end of House of Cards Season 2. BUT, I'm dying to know who

enhanced it! I can't find anything online! (...)".

I can only conclude that the "it's a ring on a cabinet" story is technically true

and a sound engineer has actually used it to enhance Kevin Spacey's desk

banging sound, but they conveniently "forgot" to mention the relation between

these two facts. One of the answers to this Quora question

mentions that "The tapping on the table with his (Kevin Spacey) ring is

associated with completing a mission or one of his plans being accomplished",

which sheds even more light into why they were banging rings on furniture to

begin with. And let's pray that the hand wearing the ring wasn't Kevin Spacey's...

None of this is mentioned in the podcast. As for the longer version

composed by Hans Zimmer,

it does not include the original soundbite at all. I

believe that Netflix is going on a PR campaign to rewrite their history, has

convinced the Twenty Thousand Hertz podcast people to just go with it, and have

so far been very successful.

And yet, I have to ask... why? Was it so difficult to come out and say "we don't

want to be associated with this sound anymore, and therefore we are releasing a

new one"? I honestly don't care about Netflix nor House of Cards (which I have

not seen), but I am kind of annoyed at such a transparent attempt to hide their

history behind a PR campaign. Or even worse, that they seem to have gotten away

with it.

I remember seeing two main camps in the old debate on whether a hot-dog is

a sandwich: those that argued "it's meat between two pieces of bread, therefore

it's a sandwich" and those that counterargued "if I asked whether you wanted a

sandwich and then gave you a hot-dog, you would be surprised". And both sides

are right! That said, one of them is more right from a language-theoretical

point of view, and that's the point of today's post.

(Spoiler: the "not a sandwich" camp is right. Sorry, pro-sandwichers!)

According to Herbert Clark a dialogue is a cooperative activity.

It is a joint activity in which both speakers try to accomplish a common

objective, ranging from something as formal as "make me understand where the

train station is" to as vague an objective as "let's kill some time".

And because it is cooperative, we do not expect the other person to be

deliberately obtuse. If I ask "Can I get you something to drink?" and someone

replies "I don't know, can you?", nobody would assume that this person has a

genuine interest in my capacity for carrying drinks. Instead, we would

immediately see this for what it is: that this person is not cooperating, that

any reasonable person would have understood what I meant, and that this person

stopped cooperating on purpose. Whether he did it to make a joke or because

he's a jerk, that's a topic for a future discussion.

There is also a principle called the "maxim of quantity" (one of Grice's

four maxims)

according to which a person will always give as much information as possible,

but not so much that it breaks the dialogue. If someone asks me where I come

from, my answer can be as precise as a specific neighborhood or as vague as

"somewhere near the border with Brazil". My answer will depend on how familiar

I believe the other person to be with South-American geography, because I don't

want to give them excessive information that they cannot handle. Again, I'm

cooperating.

Which brings us to the hot-dog debate. From a taxonomic point of

view, a hot-dog is a sandwich:

it is composed of two pieces of processed meat between two pieces of bread,

which is as clear as it gets. But this is only half the story.

The definition of sandwich came long after the sandwich itself. It is an

artificial construct designed to model and understand a set of real-life

language usages. Spoken language, on the other hand, is the real deal. Language

rules and word definitions model how we speak, and not the other way around.

All definitions are artificial and, therefore, may not always reflect the way

we actually use those words.

Bringing this all together, I would only use the word "sandwich" to describe a

hot-dog if I had a reason to believe the other person doesn't know what a

hot-dog is. If you know what a hot-dog is and I know you know what a hot-dog is,

using the word "sandwich" to speak about a hot-dog is neither maximally

informative (I am giving you less information than I could) nor cooperative

(I know which word would help us the most, but I'm not using it). "Sandwich" is

a catch-all word that can only be used when no better word exists.

Even worse: you know we both know what a hot-dog is. By choosing "sandwich", I

am actively leading you to believe that I want to offer something that can be

described as a "sandwich" but not as a "hot-dog". Fans of malicious

compliance will argue that

this is not technically untrue, but you and I both know that there's little

practical difference between "I told you a lie" and "I told you something that

any sane person in the world would understand in a certain way while secretly

using a different, opposite interpretation that I kept to myself".

So there you have it. A hot-dog is a sandwich if you stick to rigid categories

created by researchers with a tenuous grasp of the real world at best (you know,

people like me), but you are only allowed to use it if you talk to people who

never heard about hot-dogs before. Using the word "sandwich" for a hot-dog in

any other context is uncooperative, mildly dishonest, and kind of a jerk move.

People do not use the word "sandwich" like that and, since spoken language is

where "true" language usage lies, they are the ones who are using it right.